YOUR GREATEST VALUE AS A WRITER: It Isn’t What You Might Think

What element is most important when writing a novel or memoir? In ten years teaching creative writing, this is the question I’m most frequently asked. Writers want to know, is it plot? Character? Subject matter?

What element is most important when writing a novel or memoir? In ten years teaching creative writing, this is the question I’m most frequently asked. Writers want to know, is it plot? Character? Subject matter?

I insist it’s none of the above.

The most important element of craft is voice, and the most valuable asset a writer possesses is his or her individuality.

The X factor

Publishers are constantly on the lookout for what they refer to as ‘new voices’. MFA programs select students from diverse backgrounds to compose well-rounded workshops. In such situations, those doing the choosing are often choosing from among writers possessing similar levels of talent and experience. What, then, enables one to stand out from the next? When writers of similar dexterity compete, the writer with a signature style will win out over one who demonstrates competence but whose personality on the page is less distinctive—every time.

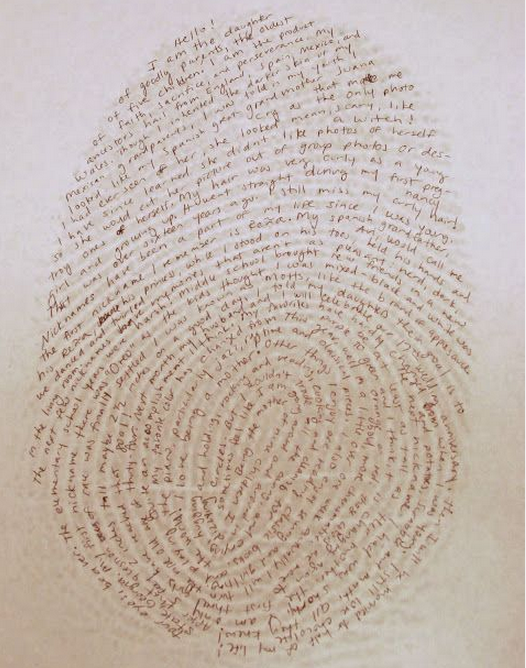

After all, the world doesn’t need more stories exactly like the stories we already have. What might the world need? Your story. Because there is no one exactly like you. And the more of your personality you call forth—your unique way of thinking, your particular obsessions—the more distinctive your work becomes. When it comes to literature, paradoxical as it may seem, the more distinctive a story, the more universal its appeal.

“Speech is the voice of the heart.”

― Anna Quindlen

Individuality is inextricable from writing.

Bestselling novelist Zadie Smith has written about the link between personality type and writing. “Personality is much more than autobiographical detail,” she notes, “it’s our way of processing the world, our way of being, and it cannot be artificially removed from our activities.” If who you are is inextricable from what you create, then your challenge as a writer lies less in thinking up ideas than in translating your unique way of processing life to the page.

But personality is only one component.

Art arises from who you are + what you notice. The plus sign is important. After all, how do you determine what to write about? If you are paying attention to the world, you notice things. Certain material will strike you. It will sink in teeth. Envenomate. In each case, there will be a reason a particular moment or certain subject struck you. Perhaps you view it differently than everyone else does. Perhaps it raises a question you find puzzling. Perhaps it touches a particular obsession or wound. Material that leads to distinctive writing always arises from a connection with its author.

On the other hand, if what you write could be composed by any other person in too similar a fashion, you aren’t yet maximizing the connection between a subject of inspiration and what about it strikes you. Those new to writing voice frequent fear of others stealing ideas, especially if these ideas lean toward the high-concept or cinematic. I advocate for protecting intellectual property, and there are ways to do so. But you can’t copyright a concept. Until it’s manifest, it remains an idea. Moreover, if you gave fifty writers the same idea and even the same opening paragraph, you would still end up with fifty different stories. How can I say this with certainty? Because I used to give this assignment every few terms. And never once did two students draft the same story.

Your value as a writer lies less in “idea” than in interest and execution. Skill can be learned, but of equal importance is approach. If what you write is of real interest to you and delivered in your unique voice, it is unlikely another could replicate that.

From a technical standpoint, what is voice?

Voice refers to style, the quality that makes writing unique. Language is the tool writers use to create voice, but it is not voice in and of itself. And while the word “voice” indicates sound, literature is a written medium. It is more useful for creative writers to conceive of voice in cognitive rather than audial terms; voice is less about dialect or colloquialisms than about style of thought. Voice refers to how a character thinks rather than how a character sounds (and, by some extension, how an author thinks.)

For example, if you are writing through the point of view of a child, you must delve into that character’s thoughts. Rather than limit yourself to the vocabulary of a ten-year-old, you instead might strive to inhabit a child’s sensibility—that innocence or quality of magical thinking characteristic of childhood.

Voice-driven fiction dominates the landscape of American literature in no small part because Americans hold individuality in high esteem. The hallmark of books from The Member of the Wedding and The Catcher in the Rye to Lolita, Jesus’ Son and Middlesex is that, in each, the telling ends up being as important as the story being told. Each of these books offers a glimpse not only into the minds of distinct characters, but into the mind of its author—through language and technical choices, we become acquainted with what intrigues and repels the writer, along with what reflects the social context out of which each book was created.

The telling takes on even greater importance in memoir. As Jonathan Franzen noted, “There are only two things that can make a memoir really good. One of them is great material that is true . . . the other thing is if you’ve got a great voice, if you’ve got a great tone going. That’s it.”

Bret Lott also stresses the role voice played in the signature styles of acclaimed American authors: “What made Hemingway’s and O’Connor’s and Carver’s writing important and meaningful and real is that they wrote from their own chair. They didn’t walk away from themselves in order to go sit in someone else’s. Lesson: Don’t leave you to go find your point of view and your story. You are all you have been given. This is who you are, and from where you ought and need to write.”

How can I find my voice?

Identify what you love, why you write and what influences shape your experience.

1. Your Passion

Make a list of your five favorite books and five favorite films. Identify elements they have in common. (Exotic locales? Love triangles? Epic scope?) Notice if a particular theme or obsession or question arises again and again. What you are drawn to speaks to what you should be writing.

.

2. Your Purpose

Tracking Wonder founder Jeffrey Davis defines purpose as a “more-than-me yearning” and cites studies performed at Harvard Business School that rate purpose as one of the most important motivators for sustaining momentum on any project over time, outranking both performance and profit. Writers must identify a purpose, in life, and writing. Examine: What are you writing for? Once you identify motivational factors—both ego-driven and altruistic—you’ll notice patterns in your work—questions about the human condition that pique your interest, as well as the subject matter through which you enjoy exploring them.

.

3. Your Distinctions

Each writer functions best at a specific intersection of time, place, and eternity, according to Flannery O’Connor. Why not put specificity to work in your favor? You’ve been born into a specific era and culture. You possess distinct life experiences and a certain style of thought. You remain steeped in all of the art and media consumed in your eighteen or eighty years on earth.

.

Try listing ten things that make you distinct. They need not be dramatic, they only need be specific. What generation do you identify with? In what religious tradition were you raised? What were your favorite songs in high school? Once you have your list, use items as jumping-off points. Draft into questions such as: How has being a second-born impacted the way you see the world? What would have been different if you hadn’t been born in Arizona? You may find yourself more interesting than you realize.

Likewise, explore exercises to connect with your artistic ancestors: what do you share in common? How can you engage with these to forward your writing project?

Ready to achieve your writing goals?

If you’d like a writing coach to help you better connect with your personality type and creative process, reach out and let’s chat.

Explore our professional editing services for expert feedback at both the developmental and line level.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Submit

LET's GET STARTED.

Hi, I'm Carol,

an Arizona-based editor who turns ideas into art. Need to get your book publication-ready?

Receive

Copyright © 2022 The Writing Cycle

Brand Photos By: Hayley Stall Matt Allen

Sign up for our quarterly newsletter and gain immediate access to free writing resources.

Stock Photos By: Styled Stock House

Thank you for this guidance and article, such a serendipitous gift offered in my feed on Facebook today. I’m going to play with the exercises . . .

Thank you for this article. You’ve helped me find another way to help writers in the memoir workshops I facilitate.

Hey! I know this is kinda off topic nevertheless I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in trading links or maybe guest authoring a blog article or vice-versa? My blog discusses a lot of the same topics as yours and I think we could greatly benefit from each other. If you might be interested feel free to send me an email. I look forward to hearing from you! Superb blog by the way!

Nice post. I learn something new and challenging on websites I stumbleupon everyday.

It’s always exciting to read content from other writers and practice a little something from other sites.

Your blog is a constant reminder that we are capable of achieving greatness.

Thank you for this insight.

I am going to write a memoir which details my intrepid travel adventures throughout both remote and well known places of the world 30 years ago. All true and taken from travel journals written during the journey.