Connect with Your Artistic Ancestors

Can your influences help you around writer’s block?

In Do You Have Writer’s Block Because You Are Writing in America?, I explored systemic baggage which impacts any American who sits down to write.

When it comes to writer’s block, writers are afraid, but not only afraid. They are also:

Disconnected from a larger purpose for creating.

Disconnected from one another.

Disconnected from creativity in daily routines.

And disconnected from artistic ancestors.

Only in reunification can writers dismantle trans-generational fear to finally create with ease, come success or anonymity.

“One way to remember who you are is to remember who your heroes are.”

~ Walter Isaacson

Who Are Your Artist Ancestors?

Just as genetic ancestors bequeath flesh, blood, and epigenetic memory, artistic ancestors are those from whom we inherit:

- Stylistic preferences.

- Thematic obsessions.

- Connection to a subconscious well of creativity.

- Membership in non-genetic lineages which enlarge our work.

We’re all a product of artistic influences.

All the media a person has been steeped in over the course of a life shapes what and how a person creates as much as life experiences and psychology. Understanding exactly what inspires you can help you understand where you fit in, as well as provide a reliable catalyst for future creative endeavors.

Julia Cameron notes: “Heroes are personal. When we inquire of ourselves just whom we admire, the answers may surprise us. We do not always admire those we should. Instead we admire those we do.”

In this post, you’ll engage in exercises to reconnect with your artistic ancestors and to hone in on what guides your art at a subconscious level.

You’ll then consciously invite these creative forces into dialogue with your own writing, so it may gain power. In so doing, obsession over professional status or the success of any particular piece of work should subside, replaced by steady engagement and a sense of connection to a larger whole.

Remember: the contemporary Western emphasis on a maximized self places particular stress on writers, who work in isolation rather than in collaborative environments.

Writers yearn for success and validation, yet alienated from tradition, such emphasis on innovation—being “first,” “best,” and “only,”—distorts the reality that all art represents a forwarding of form and collective experience. When we acknowledge nothing is new under the sun, we are better able to release pressure to be “the” voice of a generation and relax into being “a” voice.

Writer’s block dissolves when we embrace our place in a mosaic, contributing whatever variations on viewpoint and theme strike us as story-worthy. When we allow ourselves to be guided, we are no longer ‘going it alone.’ When we write not only from ourselves, our writing gains appeal and universality.

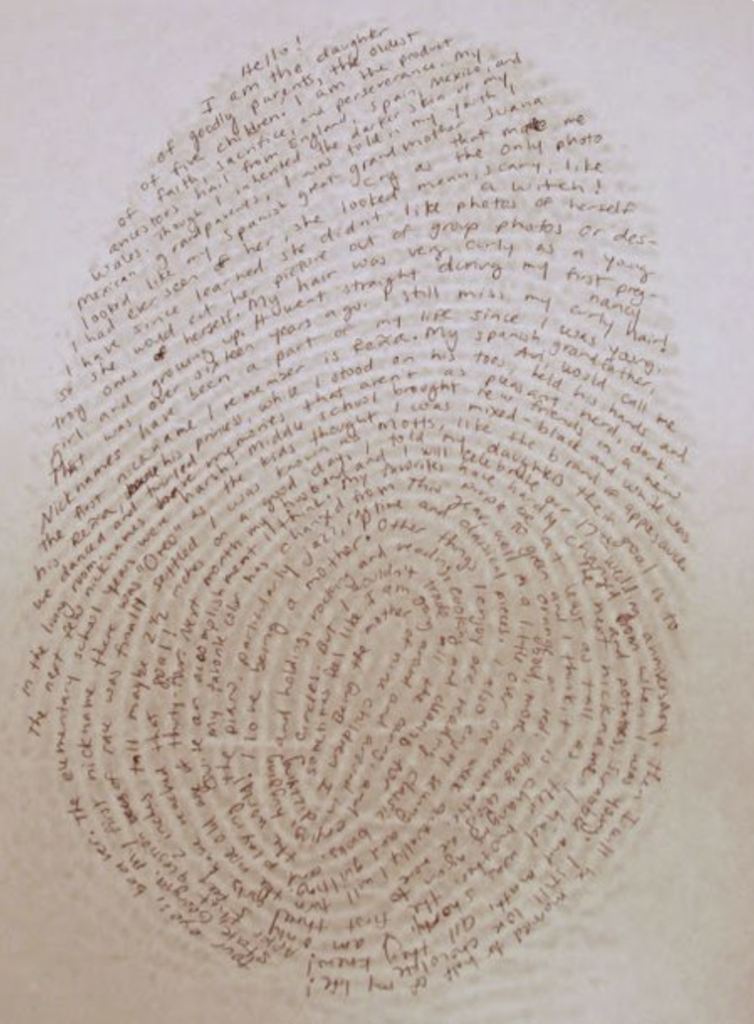

“Heirloom implies something handed down that ties together. Like a chosen family, writers can work to more fully realize other lineages we belong to: aesthetically, historically, medically, spiritually, etc.

When writing, consider: what thread is strung through you?”

ID YOUR INFLUENCES

First, compile a digital file of art and media that has had the greatest impact on you. Do not try to identify why a particular piece has struck you at this point. Simply gather work that has influenced your life.

Dissolve delineations between “high” & “low” art to best represent inspiration drawn from all around you. Redefine what “art” means to you.

Understand your most significant influences will likely come from a genre outside the one you work in.

Trust your intuition.

After the gathering, review the file. Note how pieces interact with one another. Then, journal answers to one (or more) of the following questions:

- In addition to the cultural and familial, can you identify other lineages you belong to: aesthetically, medically, geographically? How many lineages are you carrying within yourself?

- If you had to select three works that transformed you in some way, what might these be?

- To what styles do you find yourself drawn?

- What songs make up the soundtrack of your life?

- What colors or images resonate?

DEFINE YOUR INFLUENCES

Most writers intuitively recognize art with impact. Yet we often need to more clearly connect with this signal that resonates within, telling us an influence may birth art of its own. We must better investigate the connection between who we are + what strikes us in order to take the next steps of engagement and creation.

Painter Maria Woodie insists that to learn from the work of an Artist Ancestor, you must apply the analytical part of your brain to pinpoint what it is that makes his / her / their work specifically appealing.

Therefore, it’s time for a bit of categorization.

Examine three creators (in any medium) who have shaped your style. How would you categorize their work?

- Create a sentence of purpose.

If you are struggling to define your own creative vision, take a look at the lives of two or three artists you admire. Pick up a biography or read an interview with each. Pull out key quotes describing the artist that echo your aspirations. Reinterpret these lines to describe your own work.

Experiment with filling in one (or more) of the following phrases to develop your own “sentence of purpose:”

“I feel close to him because __________________________________.”

“Her work with ____________________ represents ___________________.”

“I channel him when I __________________________________________.”

“I have always been inspired by their ___________________________________.”

“Like _________________, I ________________________________________.”

“I admire artists who _____________________________________________.”

2. Identify shared themes.

What do your gathered influences have in common, beside living alongside you? Can you recognize recurrent themes you find yourself drawn to, despite diverse media they may be drawn from? (You’ll be surprised how many favorite works share the same tensions.)

To identify themes, look for binaries. Binaries refer to opposing forces: life/death, hope/despair, reality/fantasy, individuality/conformity. In writing, every protagonist or narrator is torn between some form of these. As a plot thickens, a main character often tacks from one to the other. In the end, s/he/they must choose with which to align.

Which binary forces recur in both your and your influences’ art? Is there a reason these beckon? Such themes represent a thread binding you to your artistic ancestors.

ENGAGE YOUR ANCESTORS

Once you’ve gathered influences, let them co-mingle and collide, and defined the relationship you share, it’s time to initiate a dialogue.

Play with one of the following exercises as a way to engage an ancestor across space and time in the generation of new work.

3. Make collage, the mixtape of literature.

What combination of elements can be mixed that might allow a story to surface in a new way? For example, if there are two mediums that have influenced you, could you make art in one directly inspired by the other? What other form could inspire a writing project, and in what ways?

Maggie Nelson’s book-length essay Bluets contains lyrics, quotes, definitions, folklore, and facts about the color blue surrounding her narrative about depression and heartbreak, all arranged in bite-size units that form a text collage, which gains resonance from metaphor and metonymy. Moving pieces around alter their meaning.

Stephen Dunn’s water & power creates a collage from varied voices rising up out of official documents: exit interviews, field reports, names of dead/missing veterans, even cartoons that explore subversive forces within the authoritarian structure of the Armed Forces.

4. Get in conversation.

The poet Cea Jones via their course HEIR/looms prompts this concept of a DUET – picking an author and engaging in direct conversation with one of their pieces as it regards your own experience. For example, the poet Tory Dent wove her personal journey with AIDS into lines of Sylvia Plath’s famous poem, “The Moon & the Yew Tree.” The conversation between writers made a typical illness narrative layered, textured, and more interesting.

How might you pull from other voices to allow your own experience to deepen and widen, so it is no longer the story of a person alone, but of the larger human experience?

Pick a mentor text (which doesn’t necessarily need to be text!), and write yourself into it. How does your voice engage with or DISRUPT what you’ve chosen? Does it serve, as Jones asks, as: “silent dance, duet in different languages, or two mirrors held up against each other?”

5. Structure using ancestral forms.

Innovation is almost always the result of uncommon combination. America’s most brilliant innovations have resulted from disparate cultures colliding. Such collisions create musical forms, cuisine, literary and film genres, and technological inventions never before experienced.

Since theme is often something shared with artistic influences, might you apply the structure of a thematically-related ancestral art-form to a current work-in-progress?

Beth Piatote choose to structure her novel-in-stories The Beadworkers to mirror her tribe’s Salmon Ceremony. The order of this Nez Perce Feast served as the book’s foundation. Her book is also interactive, almost a game in places, highlighting a-linear and cyclical functions of ritual, beadwork, and storytelling in collective cultures, while also providing a recognizable point of entry for a readership often overlooked.

Can you lay a structure drawn from one artistic lineage you are carrying within yourself over another project?

ARTISTIC INFLUENCES IN ACTION

Who are your artistic ancestors?

Share in the comments any art or artist that has inspired your writing or way of being in the world.

Let us know ways in which you’ve honored or incorporated these into your own projects.

If you share yours, I’ll share a post exploring mine.

WANT MORE UNCONVENTIONAL WAYS AROUND WRITER’S BLOCK?

READ ON TO LEARN:

I. How American cultural mythologies cause writer’s block.

II. How to enter the brain wave state for optimum creativity in 90 seconds.

III. How to define your life purpose . . . and how writing fits in.

IV. How MBTI Personality Type affects writing style and skillset.

V. How to reclaim writing as an everyday activity.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Submit

LET's GET STARTED.

Hi, I'm Carol,

an Arizona-based editor who turns ideas into art. Need to get your book publication-ready?

Receive

Copyright © 2022 The Writing Cycle

Brand Photos By: Hayley Stall Matt Allen

Sign up for our quarterly newsletter and gain immediate access to free writing resources.

Stock Photos By: Styled Stock House